LOW BACK PAIN INFO - PART 2

4. EXAMINATION

In part 1 of this series, I talked about how imaging can show things that are not causing your pain, which can lead to diverting attention away from the real problem and may cause unnecessary surgery. That being said, a thorough, nit-picky physical examination by someone with experience treating varied back ailments is imperative! Even if an exact diagnosis cannot be made, a good hands on examination will tell a practitioner many things. There are many things to look at, but the first thing is to rule out any serious pathology such as heart problems or cancer that could be causing the pain.

Following is a list of things that should be considered during a back evaluation. Please note this list may not be totally complete.

· Rule out serious pathology

· Discuss onset, nature, progression of the pain

· Discuss what makes it worse or better

· Discuss what happens over 24 hours

· Discuss where on your body the pain occurs and how it affects you

· Discuss if the pain seems centralized, in one spot, radiates or moves around

· Discuss how it affects your functional activities

· Neurological screen

· Movement screen

· Range of motion screen

· Strength test

· Provocation tests

· Asymmetry of muscles or movement

· Palpation and skin glide

5. TREATMENT

The Medical Community Guidelines for treating low back pain developed through randomized control trials are as follows:

· Start Treatment Early – less than 4 weeks from onset.

· Manual Therapy (manipulation, mobilization, massage) but combined with active therapies – manual therapy with exercise gives better results than either manual therapy alone or exercise alone.

· Exercise-varied according to the problem but often trunk stabilization, trunk coordination, strengthening and endurance. The medical community now believes that whatever movement activity a patient will actually do is best for that patient. (Interesting!)

· Walking – but again walking combined with exercise has shown better results.

· Traction-showed few short or long term benefits and is NOT recommended as a single treatment

· General Education and advice -strongly recommended for understanding pain, home exercise and self-management, as well as provide positive reinforcement of likely recovery

· Counseling – if needed

6. ADDITIONAL TREATMENT OPTIONS

Other treatment modes available, not mentioned much in the general medical guidelines, which I have found to be successful in varied combinations include:

· Cold and Heat

· Modalities such as ultrasound, varied forms of electrical stimulation (non-painful) and diathermy (a form of deep heat). (Perhaps a bit old fashioned but combined with manual therapy and the right exercises often effective in reducing pain and inflammation.)

· IASTM (Instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization)- a physical therapy technique using specialized tools to treat soft tissue injuries, breaking down scar tissue and adhesions, reducing pain, and improving range of motion by stimulating healing and blood flow through targeted strokes on muscles, tendons, and fascia.

· Cupping – an ancient form of alternative medicine that involves placing special cups on the skin to create suction. This suction is believed to increase blood flow, relieve muscle tension, and promote healing in the treated areas.

· Acupressure or acupuncture

· Myofascial relief techniques – including use of rolls, balls, active movements

· Qigong

· Tai Chi

· Gentle Yoga

· Anything else that helps

7. THOUGHTS AND ADVICE ON BACK PAIN DERIVED THROUGH PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

In this section are the points I really want to set forth…

ONE SIZE DOES NOT FIT ALL -Treatment should be based on each individual’s unique symptoms, lifestyle and time availability and not be cookie cutter for all. In my experience finding the correct treatment usually takes some to a fair amount of trial and error. (Less trial and error when working with someone attuned, knowledgeable and experienced in finding what is causing the pain and treating low back pain.) It should be a joint effort between patient and therapist.

(Personal story #1…After a year of significant back and hip discomfort I could not make go away myself, I finally went to an orthopedist. An x-ray showed some age related narrowing of spinal joint spaces but nothing else. The doctor swore the physical therapist in his practice was amazing. This therapist’s examination consisted of having me lean forward and backward. Three seconds, if that much. That was the full extent of his examination. He had an aide give me a standard, pre-prepared set of exercises (all of which I had already tried) and applied the same modalities I told him had not worked in the last year. After two wasted visits I went back to the drawing board for myself. He had not listened to me as to what had not worked for me. I had gone to him for expertise I felt I did not have at the time. I then took the matter back into my own hands and signed up for several clinical courses for back pain with techniques I had not been familiar with. I was able to put together a new plan of action that worked and continues to work for me for that problem. Best of all this added many new “tools” and techniques to my practice to help others. I keep taking more courses regularly on the subject. Win, win all around.)

· ONE AND DONE PROBABLY NOT - In my experience back pain is rarely a one time deal that can be permanently fixed. I find it tends to come and go more often than not. It is my belief that one should really take the time, effort and trials, with or without help of a professional, to find out what makes your individual pain go away and how you can manage that yourself. You then follow that routine until the pain is gone and you feel like you again. When comfortable you may be able to slack off on your program. If your pain starts to come back, you get back to your program again. Learn what you can do to prevent it from coming back. BE AWARE that it is coming back before it starts to get too bad and do what you must to keep it from progressing. What worked the first time should work again -IF- it is the same problem. (If it is a new problem, you may need to start the learning process again to find what works for the new problem.)

· IF IT IS NOT WORKING, DON’T WASTE YOUR TIME AND MONEY – Yes, you need patience and most likely nothing will work immediately. It may take a few weeks to assess what is helping and what is not and improvement most likely will be gradual but keep in mind there are some lucky times when there actually is a quick fix. If that is the case, you do not need to read further.

However, if you have been subjecting yourself to a procedure or doing an exercise routine or going to therapy or a chiropractor for weeks and months or even perhaps years without significant results with hope of a “breakthrough,” I can almost assure you it isn’t going to happen. If whatever you are doing isn’t working, it ISN’T WORKING. STOP DOING IT!

(Personal story #2 -I worked a short time for a doctor who did deep needling. My job there was to give a hot pack and massage to make patients feel better after the very painful and expensive needling. One woman who came in in a wheelchair had been coming for almost 2 years. Every week she told me the doctor said she was going to make a breakthrough soon. I wanted to shake her and ask her why she was still coming and subjecting herself to this painful procedure without any results. While the needling did work for some, it clearly was not working for her.)

So, yes, you may need to try many things and give it a reasonable amount of time but if it is not helping you within a reasonable amount of time – try something or someone else!!!!!!

· IF IT IS WORKING, THEN KEEP DOING IT – On the other hand, if something is working for you, by all means - continue to do it. You don’t have to listen to friends and co-workers or even Dr. Internet who think they have the perfect solution for you. Only you have been in your body. You know what feels right and what does not. You can tell if “it” works or not. Don’t be afraid to listen to your body and use your OWN JUDGEMENT. (Even when doing physical therapy in general, for any issue, use your judgement. Therapists give an educated guess as to how many repetitions or how intense an exercise should be for you. It it doesn’t feel right for you, alter it - but do let them know.) You possess intuitive self- healing/preventative powers. You do. Make use of them.

(Personal story #3-These last 2 blogs on back pain were sparked from the following story a good friend told me. Right before her wedding, my friend experienced some back pain. She did a short course of physical therapy and was discharged with a home exercise program. Nine years later a teaching assistant in her second child’s kindergarten class had the same last name as the therapist she had seen. In speaking with the assistant, she learned that the teaching assistant was the wife of the therapist she had seen. My friend gleefully told the wife that she was still doing the exercises he had given her and that she remained pain free. The next time she ran into the therapist’s wife, the wife told my friend that she mentioned their conversation to her husband and her husband said that she didn’t have to do the exercises anymore.

Before I write “NO. DON’T STOP,” (and I will,) I want this audience to know that my friend is now in her seventies and continues to do these few exercises every morning. She has had no back pain episodes since before her wedding that I know of. How many people do you know in their seventies that have no back pain? I am not sure I know of any. I definitely advise her, “YES, keep doing those exercises! They are working for you.”)

Thus, I think it bears repeating. If something is working for you, keep doing it for as long as it is working or your judgement tells you to.

In closing these 2 blogs on back pain, I hope I have given you some new information and awareness of what is out there and some encouragement to self-advocate when seeking help for your back pain. I am happy to answer any questions you may have on this subject via email. Feel free to contact me at fnogeept@gmail.com.

DISCLAIMER: This blog content is for informational and educational purposes only, not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and users should consult a doctor, especially for emergencies.

Low Back Pain Info - Part 1

SOME GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR BACK PAIN

Back Pain can be undaunting - no doubt about it!

If you suffer with back pain, you probably already know there is no one way or even any standard way for that matter, to fix it. Strep infections have penicillin. There is no “penicillin” for back pain. Finding a clinician who can help relieve some of your symptoms is certainly a trial itself. Many, if not most of us, have been there.

In Part, I will provide some standard and recognized guidelines from the medical community to know and think about if you suffer from back pain.

In Part 2, I will provide some of my thoughts and opinions from my many, many years of experience in treating back pain symptoms (including my own,) and from changing my approach to treating back pain umpteen times.

1. GENERAL PRACTICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FORLOW BACK PAIN

While there are many things that clinicians and physicians disagree about in the care of back pain, here is the somewhat official list of what is agreed upon for back pain in the medical community:

· Rule out specific spinal pathology or other pathology that can cause back pain

· No routine use of imaging for non-specific pain - (see #2 below for more info on imaging guidelines and reasoning behind it.)

· High quality patient education – including pain science education

· Physical Exercise – Movement or activity should be based on patient preference or what patient will actually do. Active motion is better than passive.

· Manual Therapy (manipulation, mobilization, massage) combined with exercise is best, better than exercise alone.

· Early return to activity

· Caution with Opioids

· Promote Self-Management - (Freda agrees strongly with this one, once what works for your pain is figured out.)

· Assess and manage psychosocial factors – refer for psychological or cognitive therapy when indicated

2. IMAGING

WHEN IMAGING IS NOT RECOMMENDED

In the absence of red flags, imaging is no longer recommended for:

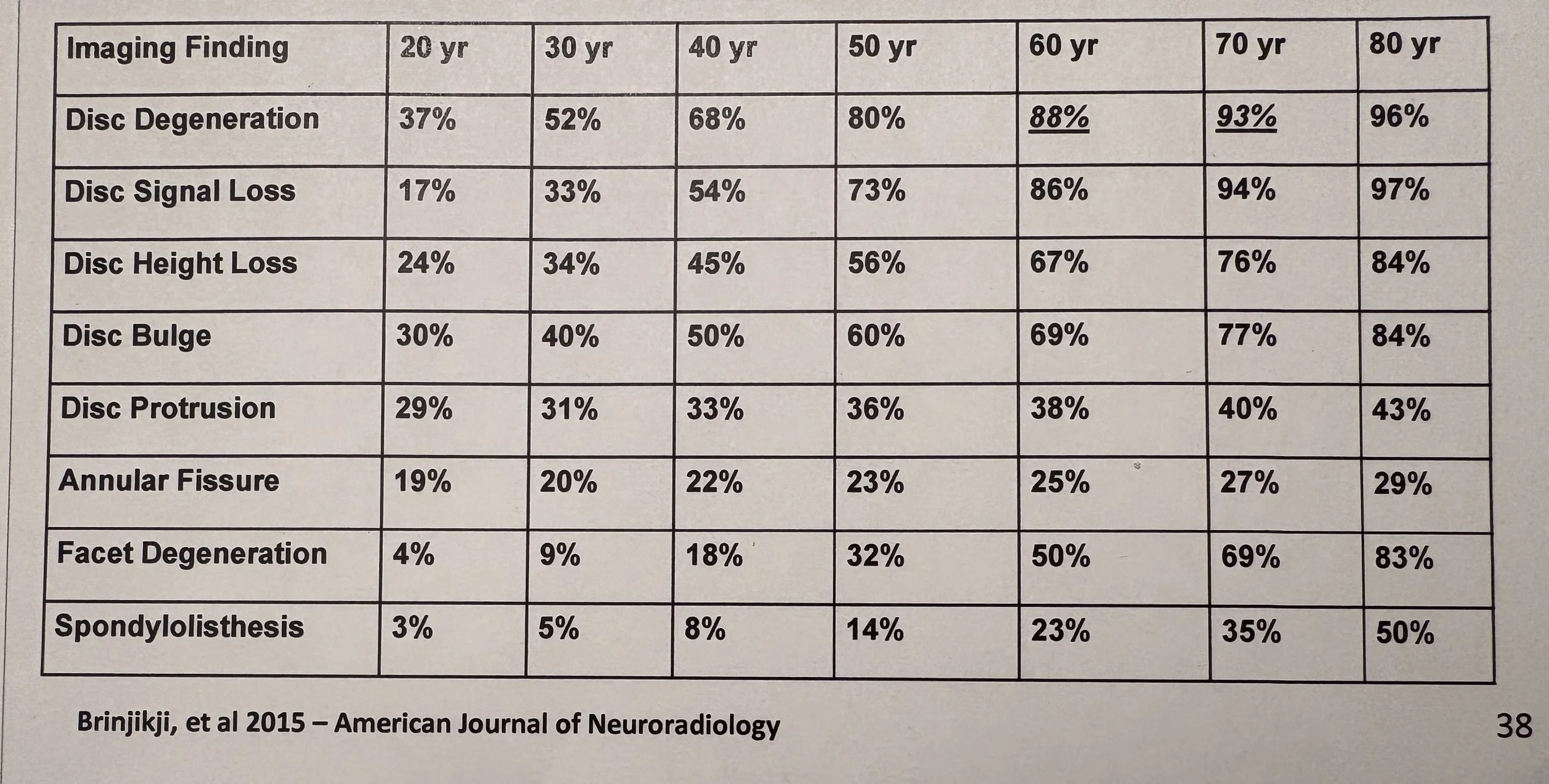

· Acute pain within the first 30-45 days - (“Imaging for low back pain in the first six weeks after pain begins should be avoided in the absence of specific clinical indications (e.g., history of cancer with potential metastases, known aortic aneurysm, progressive neurological deficit, etc.). Most low back pain does not need imaging and doing so may reveal incidental findings that divert attention and increase the risk of having unhelpful surgery.”) American Society of Anesthesiologists – Pain Medicine January 21, 2014. * SEE CHART BELOW *

· Low back pain with referred pain (as in some hip or butt pain) especially in people over age 65. (Referred pain often increases with walking and decreases with rest.)

· Chronic low back pain related to generalized pain

CHART *

The following chart shows image findings in people who have NO back pain. Various degrees of spinal degeneration are present in high proportion without symptoms. Thus, what might be found in imaging may not be causing the problem and can divert attention away from the problem or increase a patient’s anxiety about their back pain.

WHEN IMAGING IS RECOMMENDED

Imaging is recommended for:

· Low back pain with radiating pain

· In progressive neurological conditions

· When surgery ss potentially indicated

· When one is a candidate for epidural injections

· With other clinical findings such as central canal stenosis with bowel and bladder changes, root compression with muscle weakness that does not change with movement or position changes

3. ACUTE PAIN vs CHRONIC PAIN

Back pain is considered to be acute if you have had pain for 3 months or less.

Back pain is considered chronic if it has occurred for 3 months or more. Chronic pain may be more associated with other generalized pain or psychosocial issues.

Intermittent, “on and off” pain is not particularly noted in the literature, but Freda has seen this a lot and will address in part 2.

STAY TUNED FOR PART 2 WHERE TOPICS WILL INCLUDE INFO ON EXAMINATION, TREATMENT AND FREDA’S THOUGHTS ON LOW BACK PAIN THROUGH EXPERIENCE

LESS IS MORE!!!

Are you getting enough exercise? Am I getting enough exercise? Probably not. Most of us are inherently lazy. And besides, we all know “life gets in the way.” Right?

But perhaps, if you are getting and paying for physical therapy for an injury, fall or need to work on general strengthening and mobility, the question should be, “are you getting the proper exercise?” Are you getting a therapeutic dose of exercise that will actually help you improve? The answer to this question is also “probably not.”

In my many years of practice, I have worked in various settings and in most of them I would venture to say the proper amount of exercise to facilitate improvement is not being given. Especially in outpatient practices, I have too often seen a patient initially get evaluated by a therapist and put on a program. In subsequent visits the patient is either working on their own or with an aide or assistant following the initial directions that were given. Six weeks later the patient is still using the same 2 lbs. weight they started with.

Does your therapist or trainer tell you to do 3 sets of 10 repetitions of something or to do 50 repetitions? Where did they come up with that number? Do they tell you to do this every day?

If you can do 50 repetitions of an exercise, even 20, 25 or 30 repetitions, especially if you are trying to increase your strength, you are more than likely wasting a lot of your time.

Research and evidence based data show that to improve your strength or endurance you have to work at a moderate or high intensity level. To work at moderate intensity, you have to work at 60 to 80 percent of your capacity. This actually translates into doing less exercise and spending less time exercising! This is GOOD NEWS! You can be more efficient and effective with your exercise and see more improvement.

To increase your strength, in simple, practical terms, you only need enough weight to be able to perform a strengthening exercise for one or two sets of 8-12 repetitions, done once or twice a week. If you are able to do more repetitions than that, you need to make the exercise harder – not do more of it - to improve. For both endurance and strengthening the perception of moderate intensity exercise should be “hard” to “very hard” or a perceived exertion of 5 to 8 on a scale of 1 to 10. Your scale of perception.

The therapeutic dose of moderate intensity exercise to improve endurance or aerobic capacity is 5 days a week for 30 minutes in the perceived 5 to 8 difficulty range. Studies have also shown that doing the 30 minutes in three 10 minute increments is as effective as doing 30 minutes at one time, so breaking up the 30 minutes is an option if that works better for you.

If whatever you are doing feels “easy” it most likely is not helping you improve. It is still good for you and helping you maintain your current level of functioning, but you are not moving onward.

To recap - less repetitions and less time exercising with harder exercises is the ticket to helping you improve. Also working those exercises into your daily activities/routine rather than taking specific time out of your day to do them will also help you to spend less time doing what you need to do but don’t feel like doing.

(There are different parameters for high intensity exercise but let’s leave that to the athletes for now or email me and ask for that info if you want it.)

Bottom line. Work harder. Work smarter. Spend less time exercising and improve more than you did before.